Does Notation Matter (Part 1)

If you look back in the history of requirements methods, you can observe that the notations for capturing requirements have changed several times in the last 50 years.

In the 70s we were glad if we got requirements in written form, mostly natural language statements, like “The system shall ….”

In the 80s modeling picked up, trying to overcome the weakness of natural language as being too interpretable. We have learned to express processes in terms of data flow diagram and business objects in terms of entity-relations-diagrams, etc.

In the 90s the graphic notations changed with the advent of UML. Processes now had to be shown in use case diagrams, refined by activity diagrams. Data had to be class diagrams instead of entity relationship diagrams.

In the 00s the agile methods mainly switched back to natural language: user stories had to be written in plain English, but to be a little bit more precise, the sentences should follow the generic structure: As a «user» I want « function» so that «benefit».

In this blog I want to examine whether the way of expressing requirements, i.e. the notation you use, influences the quality of requirements. In part I of this mini-series we will look at expressing a top-level system decomposition, creating an overview of all functional requirements, before diving deeper to analyze them in detail.

An example

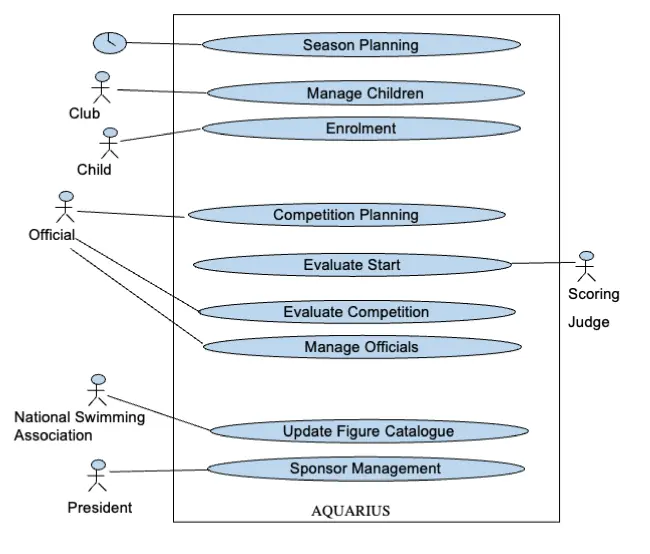

Let us contrast high level requirements for a hypothetical children swimming league, that wants to automate its manual processes by creating an IT-system nicknamed AQUARIUS. A use-case diagram could look like this:

Now, is it really necessary to use that old fashioned graphic notation, invented in 1992 by Ivar Jacobson – at a time when many of today’s developers were not yet born or in their infancy? Would not a simple list of functions also do the job. Look at the following write-up:

We have chosen slightly different names for the functions (e.g. Update Figure Catalogue vs. Update Figures), but mainly the information content of both notations is equivalent: We know we want these nine key features.

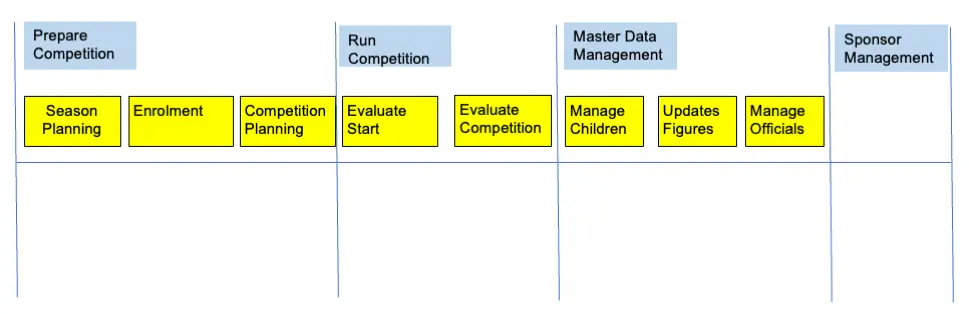

Yet another alternative would be to start creating a story map. In the following figure we just give the overview of the epics and features (since they are too big to be considered as stories yet).

You note, that we have now introduced two levels of abstraction. But that could easily also have been done in the use case diagram by putting packages around some of them. Or even easier in figure 2 by using an indented bulleted list.

So, does notation matter?

Maybe you immediately like one or the other notation of the example above – often because this is the way you were educated or learned to structure requirements in the large in the first place. But my answer is: Yes, it does matter. According to the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis language (or notation) does influence the way you are thinking about the problem at hand.

Let us look “behind” these three different notations. My way of reasoning and thinking about splitting the overall task of AQUARIUS into parts was identical in all three cases. I was thinking in processes, triggered in the environment (e.g. by children, by officials, ….) and I have given each complete process a name. This is often called a process-driven decomposition, or an event-driven decomposition (since we look at events happening in the context to determine the needed reaction of our system AQUARUIUS).

You can easily see that a use-case diagram strongly suggests this way of thinking, because you are looking for external actors (the stick figures) and just draw one abstract ellipses with the overall functionality wanted by that actor. The same could be achieved using the formula for user stories (As a …. I want …).

In the simple list in figure 2 above or the sketch of a story map this kind of decomposition strategy is not so straight-forward. You could have come up with a totally different list of functions, e.g. decomposed based on geography, (functions needed in the office and functions needed at the pool-site). Or you could have used an object-oriented decomposition (all functions to do with children, all functions to do with competitions, …).

If you think in processes to find a decomposition, then you can write them down (or draw them) in any notation. But some notations help you with a certain way of attacking the problem at hand, some of them are totally neutral and allow any way of thinking.

Summary

So, my final answer to the question “Does notation matter?” is: probably (not)! What really matters is your way of approaching the decomposition of the whole into parts. And thinking in externally triggered processes (i.e. use cases, business process, domain story telling, event-driven decomposition, user stories, ….) is crucial of coming up with a structure that fulfills the first three letters of the INVEST-criteria: They are (by construction) independent, negotiable and valuable. (Note that the other 3 letters – “e” for estimable, “s” for small enough, and “t” for testable – bring about user stories that are usually too small and too precise for a top-level decomposition. But if you write epics or features in “story style” – and ignore EST – they are good high level stories!)

Use cases have enforced that process thinking by having (external) actors, who want something from the system. The story-format enforces that by looking at “users” (I prefer to talk about stakeholders or beneficiaries), who want a process to achieve some benefit.

Bulleted lists can be created using any decomposition criterium.

Our language (or notation) strongly influences the way we are thinking. Therefore, be careful about the notation you pick. If your way of thinking is the driving force for decomposition, then every notation to express the result is OK.

In the universe of the product owner (in req42) we usually capture the top level decomposition as epics or features in the product backlog -either in simple ordered lists or in from of story maps. But we encourage you to use “supporting models” to maybe communicate this top level in a better way to your stakeholders or to help you with finding the top-level decomposition.

So remember: Agile Requirements Engineering is more than just maintaining your product backlog.