Scope is not equal to scope

This is an originally german article, translated with DeepL, but with the original german-labeled images.

Scope and context

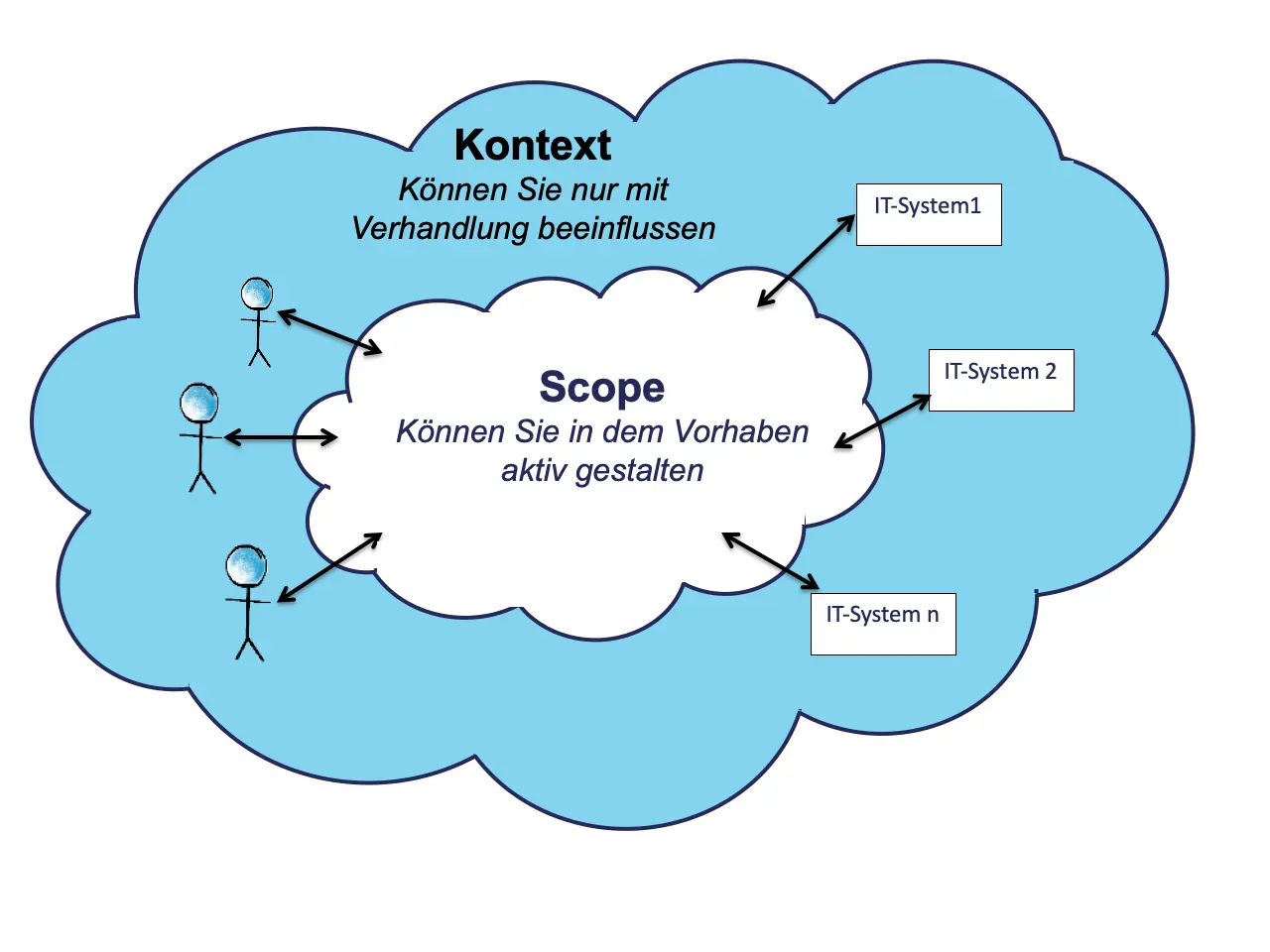

Surely you know the white lines on the tennis court around the court. They determine whether a ball is ‘in’ or ‘out’. You should also know this for your project or product development, whether a topic is ‘in scope’ or ‘out of scope’. Let’s start with two simple definitions: Scope is the area in which you, as the product owner, are allowed to make free decisions (see Fig. 1). In context are user groups, neighboring departments or neighboring systems. Changes to interfaces to these cannot usually be decided by you alone, but must be negotiated with those responsible for them. Things in the context are therefore outside your direct sphere of influence.

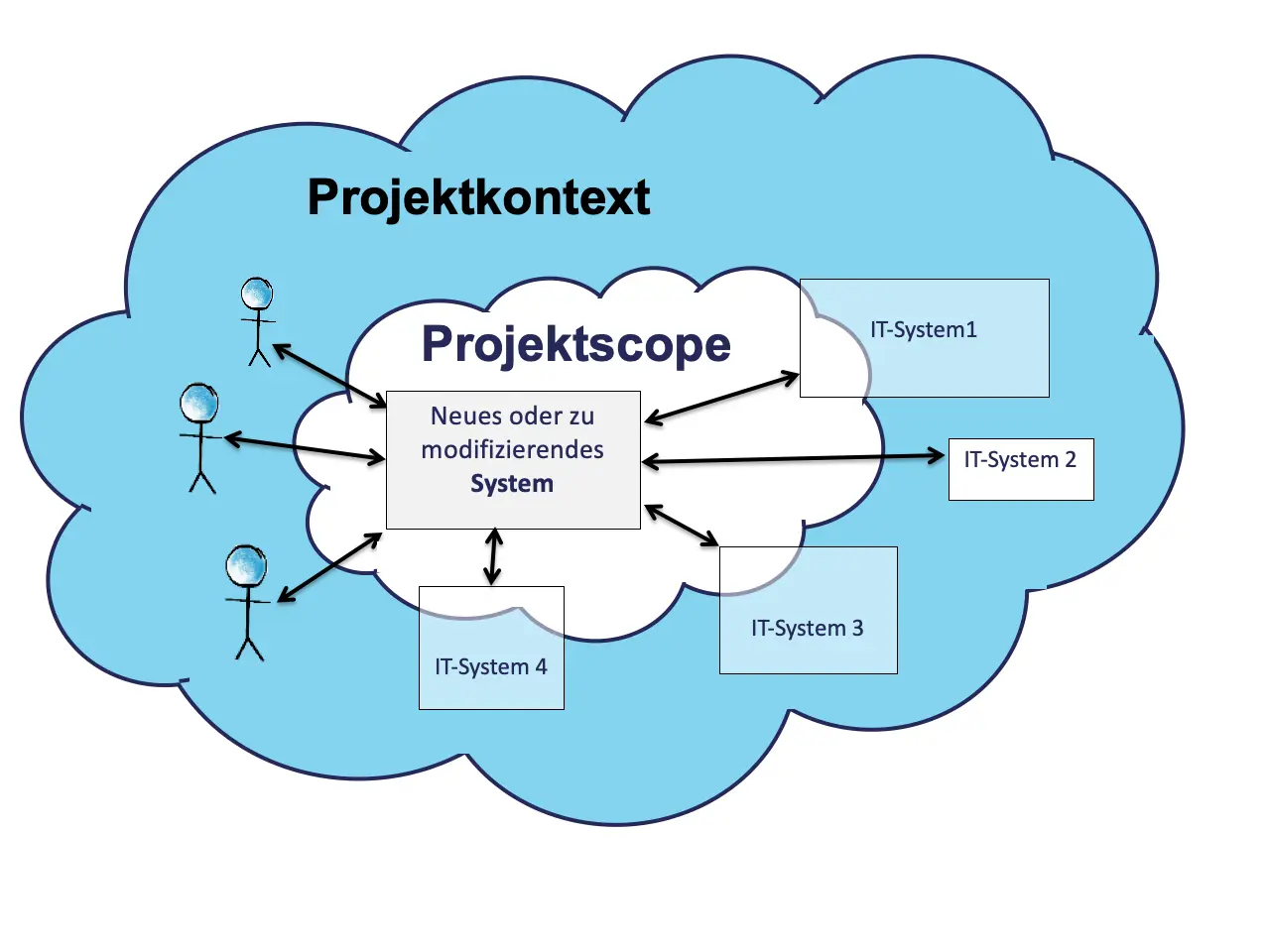

Experience shows that many people find it difficult to make this simple demarcation precisely: What belongs in our scope and with whom do we need to negotiate? That’s why we want to go into the finer points of scope definition in more detail below. When people talk about a product or system, they usually mean an IT product or an IT system. So if your task is to create a (single) new IT system, Product Scope and Project Scope are identical. In practice, projects sometimes involve several existing IT systems. You may have to develop a new system or modify it considerably, and in the process also make necessary adjustments to other IT systems at the same time (see Fig. 2).

As you can see from Figure 2, you need to define both the interfaces of the new (or to be modified) system to the users and to IT system 2, and identify the services, functionality and interfaces within IT systems 1, 3 and 4 that need to be adapted. If you, as the project manager, do not have the authority to make the necessary changes to IT systems 1, 3, and 4, your project success depends on the good will of these three neighboring systems: You need changes there, but you may not execute or order them yourself; instead, you must negotiate with those responsible for these systems. Use a visual overview (“context diagram”) of the new system or the system to be modified, together with the neighboring systems 1 to 4, in a scope definition for your project.

Notations for scope and context

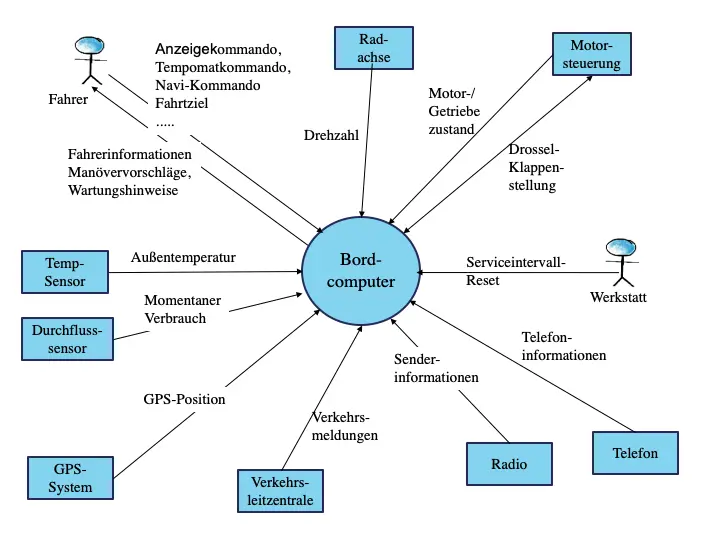

To define the boundary between scope and context, it is initially sufficient to look at the incoming and outgoing data of your system. The classic way of representing this is a so-called “domain-oriented context diagram”, [1], as you can see in Figure 3 as an example for an on-board computer of a passenger car. The system should provide the driver with typical information such as average speed, fuel consumption, outside temperature, etc., as well as enable navigation, provide cruise control, monitor maintenance intervals, and inform the driver about radio stations and phone calls.

You should identify ALL neighboring systems in a context diagram and name the inputs and outputs for each of them. An enumeration of functions (or features and epics) is usually not enough to define the scope of the product!

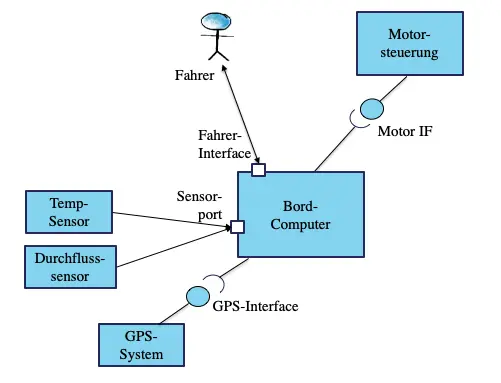

By the way, if you don’t like diagrams, [1] suggests quite a lot of alternative notations for them, in the simplest case a table with all neighboring systems and their interfaces. The important thing is that you (1.) have clearly identified your system, (2.) know all the neighbors, and (3.) understand the complete input and output at the domain level. If you’re into the graphical variety: UML offers you many ways to define interfaces more precisely. Fig. 5 now shows the use of ball and socket notation for the above example, or the introduction of ports.

We can use Figure 4 for one more tip: If a product has many interfaces, you could bundle them as analysis results. Figure 4 shows only two sensors (temp and flow). But imagine that you have several dozen sensors as interfaces. Then it is worthwhile to initially talk about only one sensor interface in the analysis and only break that down in detail during development. As another example. In the telecommunications sector, take the interfaces to roaming partners. There are perhaps several hundred of them, some of which use completely different protocols or deliver different formats. Nevertheless, they can initially be grouped into a “roaming partner interface”. As I said: interface recognized, danger halfway averted.

Development needs (interface) details

For you as a product owner, it is enough to recognize the inputs and outputs from and to the neighbors for scope delimitation. Having these interfaces explicitly identified means more than half the battle. Later in the design and development of the system, your development team will either question or decide on all the necessary details for each of these external interfaces in more detail with the stakeholders. [2] provides a lot of pragmatic advice on this.

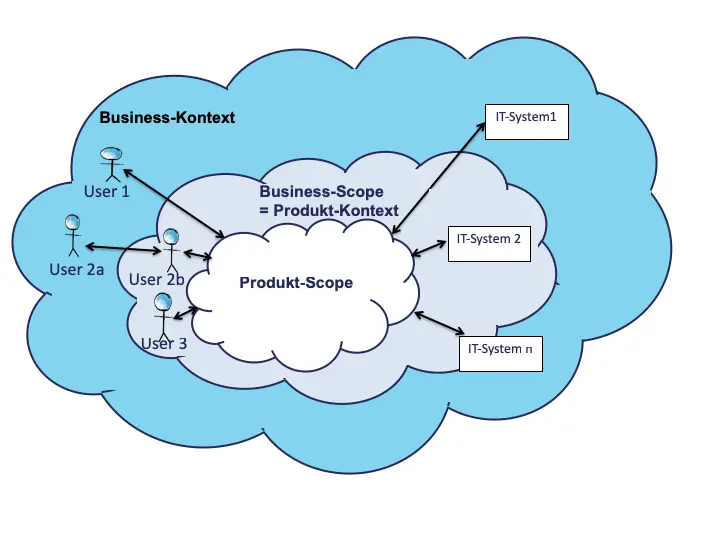

Business- and Product Scope

So far, we’ve talked more about the “mechanics” of defining scope. But we have one more agile icing on the cake for you. Thorough requirements methods distinguish between business scope and product scope: The business scope is the area of your company or organization in which you are allowed to make or propose decisions in the course of your software or system development, for example your department or division. Typically, the business scope is quite a bit larger than the product scope because you may not want to automate everything that falls within your decision-making scope. So, in collaboration between the product owner and the development team, you can determine which parts of business processes should be automated and which steps should perhaps be done manually for a longer period of time. For experienced user story experts: the “N” of INVEST stands for “negotiable”. So you should first know your business scope and then negotiate which parts of your business processes will sooner or later come into the product scope.

Fig.5 shows such a situation. “User 1” and “User 2a”, as well as “IT system 1” are outside your business scope. You have no direct influence there. “User 2b” and “User 3”, as well as “IT System 2” belong in your business scope. Therefore, it should be relatively easy to consider them when developing a new product. “IT system n” does not belong to you alone, but other responsible parties in the business context are also involved. For “User 2a”, for example, you may decide that requests will first go to “User 2b” in your department and he will fulfill this request with the new product. Later, “User 2a” may get direct access to the new system. Our recommendation is to basically open the blinders a bit wider in the requirements analysis and think about the interfaces of your business instead of the possibly limited interfaces of a product. As you can see, scope and context delimitation are not trivial in many cases.

Recommendations

Take scope and context definition seriously. Early in your project or plan, use a context diagram as a communication tool to gather feedback from your stakeholders about the important external interfaces of their system - long before you make internal decisions. Pay special attention to volatile or critical interfaces that can change frequently and without your input.

Links & Literature

[1] Hruschka, P.: Business Analysis und Requirements Engineering, 2. Auflage, Hanser-Verlag, 2019.

[2] Starke, Hruschka: arc42 in Aktion -. Praktische Tipps zur Architekturdokumentation, Hanser 2016. Many tips can also be found online at docs.arc42.org